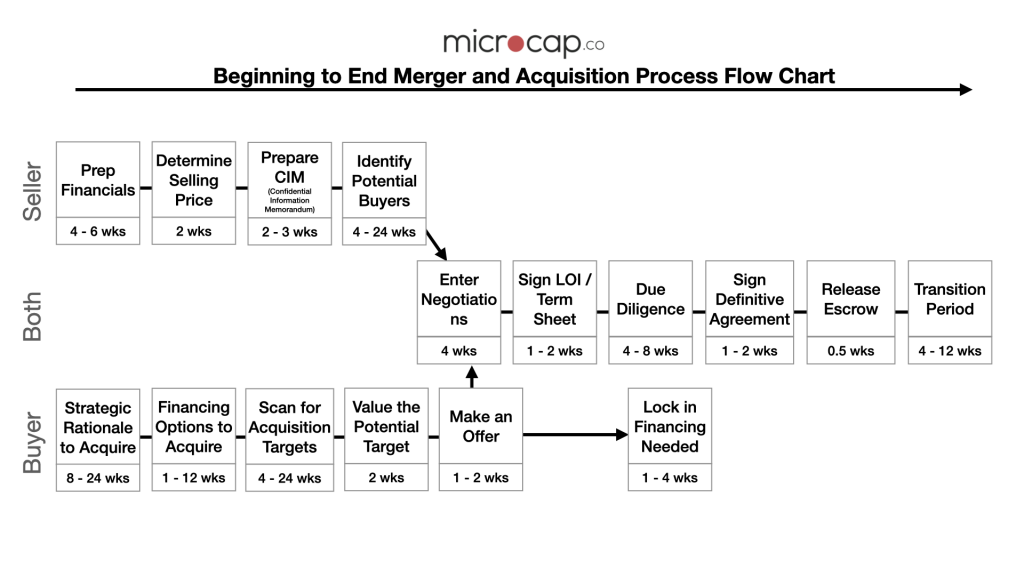

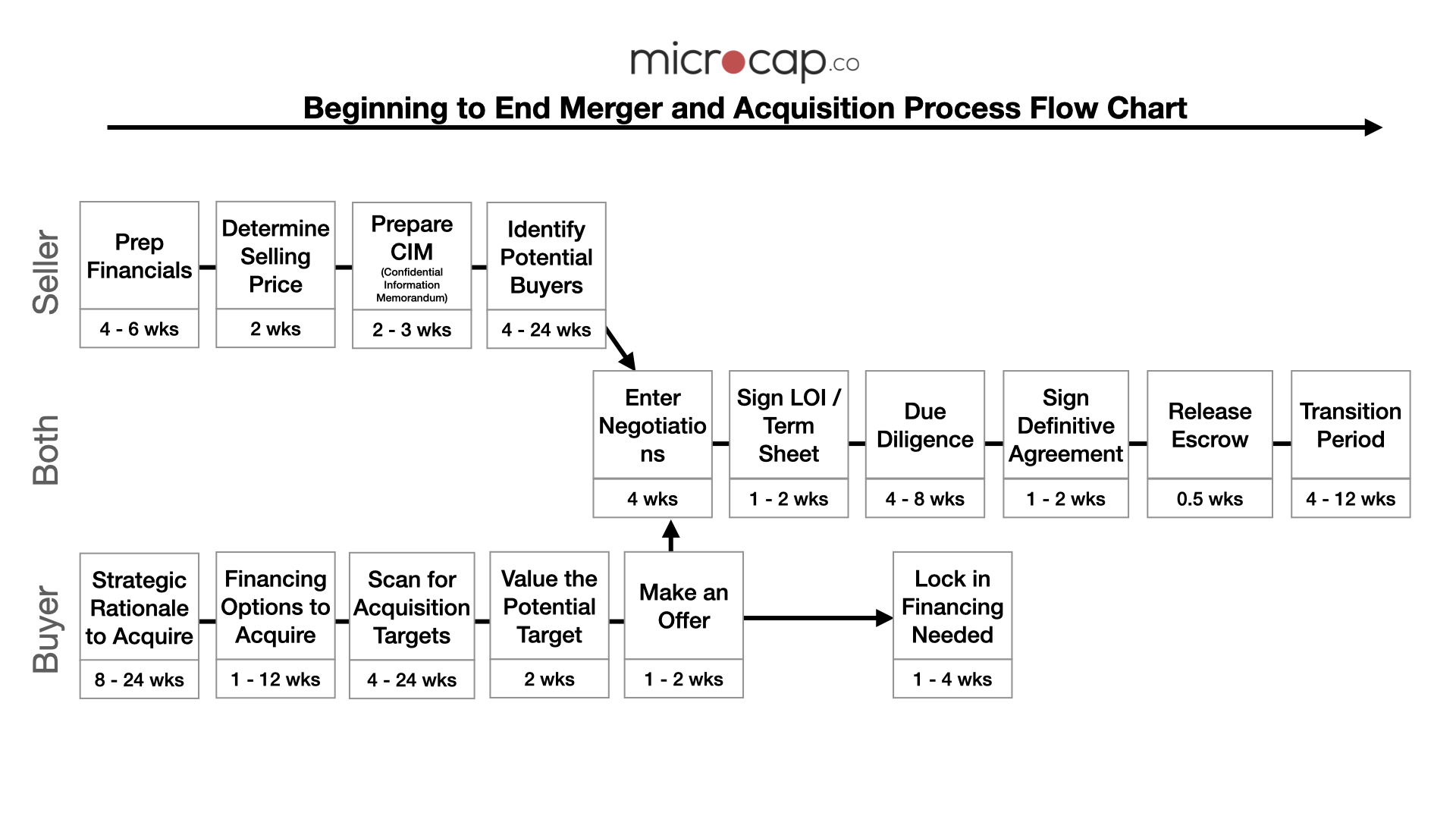

In this article, I lay out the Merger and Acquisition Process Flow Chart, and I discuss what happens in each step. This is the general process for an M&A transaction from my professional M&A experience in several industries.

Note that every M&A process is slightly different depending on whether the company is public or private, the size of the companies, industry, etc. Thus, this article should be taken as an informational and introductory guide only.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s begin.

Here is the beginning to end Merger and Acquisition Process Flow Chart. I wrote each step of the M&A process flow with the activities of the seller and buyer in mind before they find each other and begin the M&A process.

Click on a specific box in the flowchart to read more on each step of the merger and acquisition process flow.

Seller: Prep Financials

The first step after the seller has determined that it’s time to sell the business, is to prepare the financials.

These financials are used in the summary package called CIM (short for Confidential Information Memorandum) that goes out to prospective buyers. And, during Due Diligence, additional financial information needs to be provided to the potential buyers.

It allows the potential buyers to make a judgment as to whether the business they buy isn’t on the verge of bankruptcy.

If the business’s financials aren’t organized and aren’t available, there won’t even be a next step.

What does it mean to prepare and organize financials? I found that generally, there are 3 levels of financial preparedness by small businesses:

- No tracking of financials

- Some tracking but no metrics and the numbers often don’t add up

- Robust financials, has a dedicated accountant

No matter what level of financials a business has, in order to get ready to sell, at a minimum, the business should have:

- Last 3 to 5 years of P&L (income statement)

- Last Twelve Months (LTM) P&L or Year-to-Date (YTD) P&L

- Last 3 to 5 years of Balance Sheet

- 5 year Forecast of the seller’s best guess at how much the business will grow or perform in the next 5 years.

Step-By-Step and Downloads:

You can read here for more step-by-step and to download the templates.

Seller: Determine Selling Price

Before listing the business for sale, the seller should have an estimated range of how much they want to sell the company for.

In this step, the seller will engage someone who knows how to value a company to estimate what the selling price is.

This could be a financial advisor, broker, a financial analyst in the company, or the seller can learn to do this on their own.

When I worked with a mini conglomerate company that acquired and owned a portfolio of small businesses, they used a surprisingly simple tactic. If the acquisition target company had a steady operation and financial track record, they were willing to pay between 3.5x and 6.0x times the last 12-month EBITDA.

And, during the due diligence period, they did various

This is just a simplified approach. A more calculated approach should be done to value the business.

At a minimum, the two methods that should be followed are:

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method; and

- Comparable Multiples

Step-By-Step and Downloads:

- Use a simplified calculator here to get a rough estimate the selling price.

- A forecasted projection of the business and a Discounted Cash Flow should be done to value the company. Use the template here.

- Comparable valuation here.

Seller: Prepare CIM

CIM stands for Confidential Information Memorandum. It’s a spiral-bound (back in the old days when you met in person, that is) pack of 20 – 50 pages containing information about the business that is for sale.

Usually, the investment banker / broker will prepare this with the data that the business owner provides.

CIM includes the following information for a potential buyer to flip through and know more about the business that is being sold:

- Executive summary, which includes a paragraph on investment thesis (usually a paragraph or two about the potential of this business and the market)

- Background about the business

- Industry / market that it operates in and the lay of the land (i.e. market size, growth of market, typical customers)

- Products and services description

- Operations description (i.e. how do they make the products or provide services, what are the components of the operation that are required to sustain the business)

- Management structure and employee org chart (if there are key employees that know proprietary information and thus must be retained in order to keep the operation going, then they will be specifically called out)

- Shareholder ownership structure (i.e. cap table)

- Assets, including key hard assets or intellectual property. (including any tech IP will be listed here as well.)

- Historical Financials

- Projected Financials

- Value to the potential acquirer

- Competitors (maybe relative valuation; i.e. comparable multiples)

- Key risks to the business

- Contact information (banker, broker, or the business owner)

There usually isn’t information on what the asking price is or what the valuation of the company is, because who wants to reveal their hand first in the negotiations to follow?

If a potential buyer reads through and thinks that they see themselves buying this business, then the following step will ensue.

Seller: Identify Potential Buyers

If you decide to hire a broker to help you sell your business, then you don’t really have to worry about this step, because it’s the broker’s job to identify the potential buyers.

However, if you want to do the research to identify potential buyers yourself, then there are various potential buyers.

Identifying your closest competitors or asking one of your employees who might be interested in a vendor take back are 2 of the most common ways the owner of the business can sell their business without using a broker.

The above are typical steps the seller engages in before they find a buyer and enter the negotiation phase.

Below are now the typical steps the buyer engages in before they find the business they want to acquire and enter the negotiation phase.

Buyer: Strategic Rationale to Acquire

Whether you’re a business looking to grow the company by way of making an acquisition of another company or an individual, who wants to own and operate a business, you need a strategic rationale as to why you want to buy a business.

Having a clear strategic rationale as to why you want to buy a business will allow you to buy the right company that will add synergy, otherwise the acquisition will fail and you will have ended up throwing a whole lot of money down the drain.

A strategic rationale includes:

- The objectives of buying another business and how you envision this business helping your existing business grow

- A clear roadmap of integrating the potential new business and and growth plans. For example, hypothetically, when you buy this company that is located in another city, the first 3 months will be to streamline the back-end process, then the next 3 months will be to hire more talent, and then the next 3 months after that will be to train your salespeople to learn the new lay of the land in that new city, etc.

- Cash requirements, capital allocation; i.e. how much you can spend up to and still have a healthy cash flow balance.

- Important must-have attributes. For example, one of the soft attributes that might be important to you is that the employee retention at a potential acquisition target company is high and employee morale is high. If not, you might end up buying a business and all the employees quit. That might affect operations and a transition of proprietary knowledge of how the business is run that only the employees hold in their brain from experience.

Having a strategic rationale obviously does not guarantee that an acquisition of a business will succeed. But, without it, there is a higher chance of failure, since you’ll rush in, and end up with a business that is not complementary.

Buyer: Financing Options to Acquire

Before the buyer makes an offer on a potential target, the buyer needs to be certain that they have the money to pay for it. The buyer also needs to know the limitation to how much they can afford to pay for a business.

Some of the common financing options a buyer has to acquire another business are:

- Cash on hand: Many experts will say that a business should have 3 – 6 months of cash outflow requirements on hand at all times. So technically, the excess amount of cash you have in the bank above the 6 months of cash that a business will need to sustain the operations of the business is how much the buyer can afford to pay for another business. However, from my experience working for an investment firm that invested in small businesses, 3-6 months is not nearly enough. The investment firm I worked at invested specifically in small businesses that came to us because they ONLY had 3-6 months of cash left in the bank and they needed more cash. A healthy business should have at least a year’s worth, because that should give them enough time to make drastic cost-cutting restructuring changes, re-strategize and pivot, or find financing. And then the excess amount of cash on hand above the 1 year’s worth will be what they can use to buy another business should they wish.

- Bank loan: A bank loan is the other most obvious choice of financing. Banks have strict criteria such as liquidity ratios, debt servicing ratios, how much asset the business has, and the projected annual profit. Basically, the bank wants to know what the risks are that they might not get their money back. And even if the bank approves of the business loan, there are situations when getting a bank loan is not a good idea. For instance, if the business already has debt then increasing interest payments might cause financial strain on the company, especially when there is uncertainty that the newly acquired business will successfully be integrated.

- Find investors: Depending on the size of the existing business, finding investors can be one person or a group of people, or it could be an investment firm or a private equity firm. This will involve giving away shares of the company, so it should be carefully considered.

- Joint partnership with another company: To the extent that the nature of the business makes sense, the buyer can find another company to go in together to buy a business. This only makes sense if all companies benefit. For example, let’s say the buyer is a super popular yoga studio called “Yoga Me” that has 2 locations. Let’s say they identified a small boutique gym franchise with 10 locations that are selling their business. Each of the boutique gym locations is half made up of a small number of gym equipment and the other half is yoga classes. Yoga Me might want to partner with a gym franchise and buy this acquisition target, so that Yoga Me can take over the yoga side of the business while its partner takes over the gym equipment side of the business.

- Vendor Take Back: The buyer can reach a negotiation with the seller in which the buyer doesn’t pay any cash upfront, because the seller is “lending” the purchase price of the business to the buyer. There are different nuances in a vendor take back agreement, but a hypothetical example is where a buyer is looking to purchase an auto part manufacturing business. In their vendor take back agreement, the buyer doesn’t pay anything upfront to the seller. The seller retains ownership and control of the business but the buyer starts operating it. After year 1, the buyer pays X% from the profit of the business to the vendor, and that pays down let’s say 30% of the purchase price. At this time, the seller then owns 70% of the business and the buyer owns 30% of the business. After year 2, the buyer pays Y% from the profit of the business to the vendor, and that pays down another 30% of the purchase price, so now, the buyer owns 60% of the business and the seller owns 40% of the business. This continues for 2 more years until the buyer owns 100% of the business and the seller owns 0%. And, that’s when the vendor take back agreement clauses have been satisfied in full and the transaction has been completed. It’s a very useful form of financing for a buyer who doesn’t have cash, and it’s also a pretty neat form of financing for the seller, because they still benefit by getting profit from the business while retaining control of the business. You might wonder what’s in it for the seller. The seller usually gets more than the purchase price. For example, if the purchase price is $1 million, at the end of the 4 years during which time the vendor take back occurred, the seller will get $1.25 million. All hypothetical, of course, but that’s usually how it works generally speaking. Vendor take backs occur often when a long-time employee of a small business wants to buy the business from the owner.

- Royalty financing: A less widely known form of financing is royalty financing. Perhaps one of the reasons why it’s less widely known is because there aren’t many investment companies that are offering royalty financing (i.e. banks only have traditional debt financing). It is similar to debt in that a royalty investment company will provide an amount that the buyer can use like a loan amount. Where it is different is that in the case of debt, the borrower will pay back the interest and principal. In the case of royalty financing, the “borrower” will pay back an X% of their profits (or revenue or EBITDA – depends on each contract) for either a set period of time, or until the original amount borrowed is paid back, or in nightmare situations, in perpetuity. Kevin O’Leary on the CNBC show, Shark Tank, is notorious for royalty deals. Whether royalty financing is a good deal or not for the buyer depends on the economics of the business at exit. For example, let’s say a buyer wants to buy a business for $20 million, that’s making about $2 million in revenue every year. They have $18 million in cash but need $2 million to complete the purchase. They are faced with the 3 following financing options, are: A) they can give up 10% of equity for $2 million, B) they can give away a 5% royalty on revenue forever in exchange for $2 million, or C) they can get a $2 million debt financing for 7% interest for 5 years. Let’s say the buyer chooses one of these options, and then goes on to grow the business and sells it 10x the purchase price when the buyer bought it, which means the buyer is not about to sell the business at $200 million. So, which was the best deal when he bought the business? There’s only 1 option from the 3 listed which CAPS the amount that the buyer has to give away. And that’s option C) debt financing. If the buyer had chosen A), at the time of selling the business, the buyer would now have to give away $20 million, because 10% of the equity belongs to someone else. In B), if the business made $2 million in revenue in the beginning and grew that to $100 million in revenue over 5 years, then over time, the buyer had to give away hypothetically $10 million of the hard earned revenue. In C), the principal and interest comes out to $2.7 million that the buyer had to give back to the lender. So, in this case, both the equity and royalty financing were terrible deals. Anyway, all that brain dump is to say that whether royalty financing is a good financing option or not really depends on the situation.

Buyer: Scan For Acquisition Targets

Once the buyer is certain of when, how, and where they can get financing to purchase a business (or already has enough cash to purchase the business), the next step is to scan for acquisition targets. In movies, you might see a buyer approach their competitor and say they want to purchase their company. This happens in real life too, but not as dramatically. The most common approach is to hire a broker/investment banker to do the job of a) talking to their network of other brokers and investment bankers to see if any of their clients in the same industry are selling, b) scavenge the internet buy/sell business databases, c) approaches companies that they think would be a good potential target and initiates the conversation as to whether they would be interested in selling.

Buyer: Value The Potential Target

After building a potential target list and whittling that short list down to the business that the buyer is interested in purchasing, the next step is to value that business. During the previous stage, if an investment banker or a broker was used to build the potential target list, there should have already been some information provided in a CIM (remember we covered this above?). Before making an offer, the buyer values the potential of the business and gets prepared to make an offer. Here’s one simplified approach to value the business based on profit, and a more elaborate exercise of valuing the business using the discounted cash flow method.

Buyer: Make An Offer

If the seller of a business has hired an investment banker and they are running a blinded process, then buyers will submit their offer to the seller’s investment banker, then the investment banker will collect all the offers by a certain date and then announce days or a week later whom they decided to go with as the buyer. If there isn’t a formal process, then the buyer can submit an offer at any time. And, if there are no investment banks, then the buyer can also communicate the offer to the buyer directly. Typically, the buyer will submit an offer using a Letter of Intent (LOI), also known as a term sheet. Here’s a simple template you can use and some instructions on how to fill it out.

All Parties: Enter Negotiations

Now things get more interesting, because the veil is about to be lifted. In this step, the buyer and the seller go back and forth to negotiate the purchase price, conditions, the type of tender, and other things that the buyer or the seller might want as part of the transaction. For example, the seller might make it a condition that they get paid all upfront in full cash. The buyer might negotiate back and say by giving you full cash, I want you (the seller) to stay on board as an advisor to the business for 3 years, so that you’re not just running away after selling a dying business. Many things come up during negotiations. For all you know, the seller might also have some skeletons in the closet that get revealed during the negotiation phase, and that might be a deal breaker for the buyer and the transaction might not happen. This is a good time to put conditions and protections in the term sheet, such as the LOI not being binding (i.e. signing the letter of intent is a formality to act with integrity by each party, but it gives them protection to back out of it at any time). One book I had to read was Make the Deal – it’s textbook used in law school but also used in M&A training. The book doesn’t give you specific clauses you can use in your agreement, but one thing it helps is to give perspective on small nuances to think about in order to mitigate risk in entering the deal.

All Parties: Sign Letter of Intent (LOI); aka Term Sheet

After a back and forth between the buyer and the seller during negotiation, when both parties reach an agreement on the purchase price, the length of time for due diligence, conditions to satisfy before closing the deal, and other negotiation components that they agree on, both parties sign the LOI.

All Parties: Due Diligence

Once the LOI is signed, 2 things start simultaneously: the due diligence process and the initial drafting of the definitive agreement.

1. Drafting the definitive agreement: The first draft of the definitive purchase agreement is usually prepared by the buyer’s lawyers and sent to the seller’s lawyers to review. Drafting the first agreement is seen as being in a more strong negotiation position, because they can put in all the clauses they want in the beginning and see what the sellers have to say. Also important to note is that the buyers and sellers have to be just as much involved in reading through the agreement drafts because there are clauses that impact the business operations that many times lawyers might miss because although they’re thinking about protecting their client, they might not have enough knowledge about the business to make decisions on what’s good for the business. (pro tip: when the agreements are reviewed and marked up with comments or changes by the other side, they are called “blacklined” or “redlined” versions, because in Word Doc, when you make tracked changes, there are black or red lines in the left margin of the document)

2. Due diligence: In the LOI, there is a specified period of time for the due diligence, which typically range from 30 days to 45 days. This period is exclusive to the seller, so if for whatever reason, the seller digs up things during this period that deters them from buying the company, then the buyer has lost that amount of time, so this period tends to be quick. During the due diligence period, the buyer first sends a “data request” list. Some universal items on the data request regardless of industry are:

-

- 5 years worth of historical financials (including balance sheet, income statement, cash flow statement)

- Existing customer list

- Backlog

- Sales pipeline

- Employee list by function, time with the company, salary

And then depending on the nature of the business, there will be more industry specific data request items. Then, the seller will open up a “data room” where they will upload files to address the data request. As this process continues, the seller’s team will analyze the data, check off their due diligence checklist and ask for additional information. Throughout the due diligence process, the buyer will provide a point of contact in different functions (finance/accounting, sales team, operations team, etc.) to answer questions. In more organized due diligence processes, there will be calls set up where the seller’s team will go through their extensive running list of questions that they compile as they go through the files in the data room.

If investment banks are engaged to acquire a company, the investment bank analysts will go through the data with the buyer’s team. But, although they will be helpful, the buyer’s team needs to thoroughly go through and analyze the files, because they are more knowledgeable in this business space and because the investment banking analysts have a conflict of interest where they want the deal to close in order to get a transaction fee, so they could be biased and overlook some details. The end goal of the buyer is to exhaust their due diligence checklist that they had going into the due diligence process and be satisfied with their findings.

You can read my post on acquisition due diligence here and download the due diligence checklist in excel.

Buyer: Lock In Financing Need

As mentioned above before a buyer scans for acquisition targets, the buyer needs to make sure they will have the financing required to buy a company. This step never really stopped, because at that time, they needed to initiate. By now, the buyer should have locked in the financing, whichever financing option they go with.

All Parties: Sign Definitive Agreement

When the buyer’s team is satisfied with their findings during due diligence, both parties “execute” (i.e. sign) the definitive agreement. The definitive agreement can be in the form of a share purchase agreement (SPA) or purchase and sale agreement (PSA) or asset purchase agreement (APA). As mentioned before, the definitive agreement has been going back and forth between the lawyers of sellers and buyers, with both the sellers and buyers aware of every change that the other side makes and negotiating which changes to accept or reject. So, by the time the due diligence is done, the definitive agreement should now be in a place where both parties are happy with what they’re giving up and getting.

All Parties: Release Escrow

Timeline of an escrow works differently depending on each transaction, but the concept of it is the same. Just like when buying a house, the buyer will put the purchase price into escrow, i.e. a third party, and when all conditions to complete the deal are met by both the buyer and the seller, then the escrow is released by the third party, and the seller receives the purchase price. For example, after the definitive agreement is executed, one of the conditions could be that the landlord of the business facility must change the name of the lease agreement from the seller to the buyer. Or that customers must be notified. Or banks must move the name of the business owner from the seller to the buyer. These conditions basically make sure that all facets of the business are transferred over the buyer and that the seller is not left with any further obligations.

All Parties: Transition Period

Escrow might not be released until the transition period is over. So, this step might come before releasing escrow. A hypothetical transition period might be 3 months of the business’s employees training the employees of the buyer’s company. Or, it could be fully integrating the financial back-end systems. In this case, a professional project manager to oversee the integration and transition might be helpful.

Wrap-Up

The above merger and acquisition process flow chart may look simple, but each step takes a lot of effort. And there are many steps involved even before entering negotiation.

I hope you found the M&A process flow helpful. Again, every M&A process is different and the above process flow chart should be used as a source of understanding how it all works.

If you found this post helpful or if you have any questions, leave me a comment!

Here is the M&A process flow chart again – you can click on the image to download / print.